“What we do, we should do well.”

— Master luthier, Robert Benedetto

“Glenn is The Guitar Whisperer!”

It was a moniker bestowed on me by one of my customers in Savannah, GA. Received honestly, if not reluctantly, and worn humbly!

For many years I engaged with the Lutherie Arts as an amateur. The word “amateur” is an interesting word. It is derived from the Latin word amare, meaning “to love”, and later from the French and Italian amatore — “for the love of”. It is a word that in our modern language carries two opposite meanings and usages. On the one hand an amateur is someone who engages in a disciplined pursuit of some activity without the prospect or expectation of being monetarily compensated for their effort; an amateur athlete, for example. They do what they do literally for the love of doing it. On the other hand many use the term “amateur” to mean exactly the opposite, a pejorative having the connotation of someone unskilled, incompetent, and unworthy of compensation. Doing a thing and doing it well, however, does not necessarily require a price tag to validate it; certainly not if the one doing it is acting from the pure desire of satisfying their own good pleasure to create something. Sometimes the creative juices flow just to see what outcome may occur, with otherwise no set objective in mind. In a Capitalist economy compensation for work produced may or may not be a valid measurement of skill level and expertise, and is likely better assessed as a means of sustaining a certain lifestyle and level of comfort. CEOs and ground floor employees don’t have the same incomes. But they both wake up and go to work each day, whether they want to or not, whether they like it or not, because it’s their job, and they are responsible workers with bills to pay. By contrast, doing a thing simply for the love or enjoyment of doing a thing, with neither prospect nor expectation of a regular paycheck being attached to it, has little to do with validating one’s marketability and more to do with the personal fulfillment of doing a thing and doing it well. What we do, we should do well. The “why” part of the equation is not a factor.

My interest in the guitar begins in 1964 at the age of nine years old. I began studying music at age seven, learning to play clarinet in my grade school marching band. My older brother studied piano at this time, and began taking guitar lessons at a neighborhood mom-and-pop music store called Montie’s Music in Hillside, Illinois. This was coincidental with the advent of The British Invasion, which inspired seemingly every kid in the neighborhood to want to play a guitar and be in a garage band. No surprise, my brother and I were no exceptions. He switched from piano to focus entirely on the guitar, and the following year, having dropped out of band, I received my first electric guitar, a red National Newport 82, for Christmas and began my studies at Monty’s with the same teacher, Char O’Neal. Miss O’Neal was also my brother’s instructor at this time. Char was an accomplished professional guitarist in her own right, and a pupil of local Chicago Jazz guitarist, Stu Pearce. She also became the gateway for both my brother and myself to get on a waiting list, and eventually begin jazz studies with Pearce. So by age thirteen I began studying jazz guitar, a move that greatly expanded the musical palette I was exposed to beyond my generation. Mr. Pearce not only taught guitar, he also sold a selection of import guitars and basses from his basement studio in Bellwood, Illinois. And I had just enough cash saved from my paper route and summer lawn mowing jobs to buy my very own brand new jazzbox: a Univox “lawsuit” copy of the late 60’s Gibson Barney Kessell Standard model. It just made sense! So by age fourteen I now had two guitars. Having developed a studious musical relationship with the guitar, it came as no surprise to me that I would become equally interested as well in the more technical aspects of the instrument. As luck would have it, or circumstances demand it, our neighborhood garage band lacked a bass player and a bass guitar. No problem! I just hot-rodded my National converting it from six strings to four, threw some bass flatwounds on it and tuned it an octave lower. Voilá! Now it’s a bass guitar! Sort of… A very short scale bass guitar, but…

So my story is: I started tinkering with and modifying guitars in my early teens; first my own, out of curiosity and oft times necessity, then for my friends and bandmates by request along the way. Later in life, having punched the “things-you-have-to-do-in-life” list, I turned my attention to the “things-I’d-really-like-to-do-in-life” list, and at age fifty-four I launched professionally as a guitar tech for a local music store. I had evidently learned a thing or two with age because people just kept coming around with their guitars to fix. Curiosity lives long and does not fade away easy. I say, I started “tinkering” with guitars as a youngster. But I never really heard their whispers of what they were saying to me then. That would come with age, self-study, some mentoring, a lot of trial and error, and a lot of listening.

I entered the Luthiery trade professionally late in life; arguably later than most who embark on this path. Nevertheless, I entered the room with a modicum of quiet confidence in what skills I had accumulated on my own, and also with a respectable knowledge base accrued over decades as a guitarist, guitar collector, and avid student of the guitar and the guitar makers of my day. At a time well before the advent of online access to anything, an eager mind goes to great lengths to learn a thing. It’s not your successes that you learn from; it’s the mistakes and rough paths that are always our best teachers, even though the lessons and the load may come hard to bear. It is out on the edges that one meets one’s true self. About the guitar — it has always been a friend to me. And while it may not keep me warm at night, it continues to intrigue and challenge me as much now as it did when I learned my first song out of a Mel Bay book as a nine year old boy. Playing now, if only for my own enjoyment, also provides solace and comfort, a soul serenade in time of need. Some people like a game of solitaire or working crossword puzzles. I like to play and work on my guitars. I have always been as much or more interested in the guitar itself, though, as to playing it; how it is made, how it works; how to improve on its inherent qualities, and how that knowledge segues into, and informs a place where the guitar becomes a tool to create art. It is fair to say the guitar has become firmly anchored in the human story as an instrument of self-expression. Currently now in retirement I am still a student of the craft, though I have no foreseeable plans to incorporate as a business again. For me, work has become play, and I enjoy the work now as an amatuer — “for the love of” creating a thing.

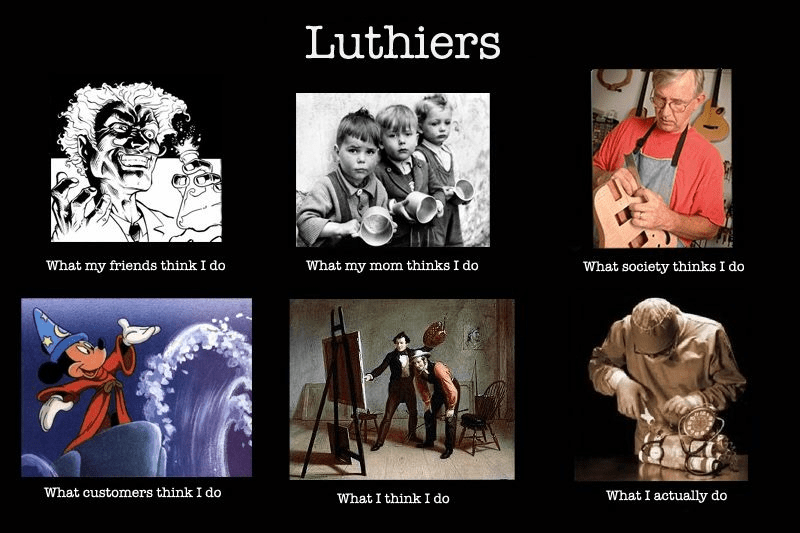

In the early learning stages of a luthier’s journey there is a formative, perhaps transformative, process taking place where fantasy and romance about the trade decreases proportionally with an increased understanding of the physical and mental labor, as well as the requisite skills, required to do the work. This is an evolutionary process that involves the growth of the luthier in his or her development as an artisan, as a person, as a business man or woman, and as a human being. Call this the “coming of age” in the crafter’s mind, which in reality is part of an ongoing growth process. Lutherie as a line of work is a labor profession; it is also a cerebral occupation; it is also an artisan craft. As a business venture — let’s just say this is a business where a lot of sweat equity and not a little money become the primary investments before seeing even just a little money as the ROI. Quite honestly, I do not know and have never met a maker or a tech who has entered this trade, or is at any time found doing it, “for the money” or for their health. There are always challenging days when you have to love it just to make it through the day! That is the work.

Lutherie, indeed any artisan or manufacturing discipline, incorporates the whole person in the work. Even in automated and semi-automated production environments, there is little room for the tech, craftsperson, or operator to go on “autopilot” in a lackadaisical or inattentive manner with respect to the work. Safety, as well as rendering a high-quality outcome with precision and consistency, demand the attention and presence of mind of the whole person regardless of the task or subtasks at hand for any given stage of the production process. With mindfulness the hands, head, and heart resonate as one to produce something beautiful, magical, and wonderful from raw materials.

We might say the mystery of creating something can become clear in a moment. But the mastery of making a thing never came in a day!

The Lutherie Arts today presents a young, diverse, vibrantly enthusiastic and intelligent community of innovative craftspeople emerging within the remnant of an element and era occupied by a few remaining practicing “Masters”. Often heard referred to as “The Golden Age of Lutherie”, these Master Luthiers have in common multiple decades-long backgrounds of crafting, restoring, and repairing stringed instruments for some of the most iconic players on the planet. Their methods are often a mixture of old school and new, while their roots are steeped in centuries old traditions. Every generation needs a few “keepers of the flame”— elder statesmen, and women, of lutherie — to pass intact the knowledge and legacies they inherited and furthered on their watch on to the next generation. One might even say a kind of vital imperative rests upon these Elders, to establish apprentice-style relationships with the Youngers in the trade, thus ensuring that guitar crafting continues to live on and thrive as both an artisan skill and an actionable livelihood. The guitar making community is one that is generally bound together in a cooperative spirit, where knowledge-share and personal growth are corollaries, and ego-trippers often get served last. The modern journeyman guitar maker does well to seek and welcome synergistic relationships with those their betters who are willing to reciprocate. A rising tide lifts all boats. To hold an ardent appreciation for the past, understanding how those technical and traditional influences of yesterday can potentially further inform and shape today’s and tomorrow’s developments in the trade, is the compass needle of modern lutherie. In the outcome this hopefully renders intelligent and resourceful innovations that contribute to making instruments that are fundamentally better than what has gone before, yet still capable of connecting with, serving, supporting, and inspiring players in ways that are altogether familiar from a traditional standpoint. There is plenty of room for experimental design in modern guitar making — how a guitar is constructed to look, play, feel and sound. But the idea of “expressionism” does not always and necessarily translate into innovations that make better guitars and serve guitar players. (The history of early Japanese electric guitar making from the late 1950’s and ’60’s perhaps provides a perfect illustration of this idea.) It remains, therefore, the age-old challenge for artisans of all disciplines: how to learn from and honor the traditions of the past while making improvements in design, materials, and workmanship techniques, rendering intact an expression of something that speaks of timelessness, the here-and-now, and genuine originality. In any case, an aspiring luthier must be committed to the improvement of themselves as well as the instruments they set out to build. He or she must remain keenly aware of, often by means of experimentation and many hours of building prototypes, what does and does not make a good instrument better, or a better instrument great. This discovery process helps shape a builder, providing the necessary discernment of how to implement a particular design idea into the build process so as to produce an end product that represents a faithful marriage of tradition with innovation. Studying historically traditional designs and being able to revise and recast them in ways that reflect product improvements without sacrificing performance, aesthetic, durability and responsiveness, moves the builder and their art further forward, adding to the history of tradition. This is a keynote aspect in the advancement of the work.

The path that leads to mastery in the craft is more of a peaks and valleys experience. Skills are developed largely from the doing of the work itself on a regular if not daily basis. Even the most seasoned makers with hundreds of certified builds on the books over decades of time, are quick to note that the learning curve is continuous and seemingly unending. Ample portions of focused process, intuitive and mentored learning, and real time spent crafting out of an idea is what comprise the lion’s share of a luthier’s energy. A modicum of space left for “mystery and mystique” is always in the mix. (Or maybe “surprise” is a better description.) Mistakes are made; and when they are they provide our best teachers. In the outcome they become either a “design change” (we sometimes call those “a happy accident”) or a do-over; both of which can be costly in a production environment.

To the uninitiated, crafting guitars can be seen as something of a proverbial black box. Pixie dust and magic wands, and all manner of esoterica comprise the art of making, modifying, and repairing guitars — or so it may appear to someone on the outside looking in who has never made, modded, or fixed a guitar.

The truth? Lutherie is a mixture of magic, disciplined focus, mad science, and a heart’s longing to create something beautiful and good. Or maybe it’s a quest for immortality. Or both, adding to the mystique.

But then a little mystique isn’t such a bad thing, is it?… Coffee, anyone?

To visit the lutherie projects blog on this site, click here or on the pic above.